Everything You Need To Know About The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull Eruption in Iceland

Everything You Need To Know About The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull Eruption in Iceland

By Michael Chapman

What caused Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano to erupt in 2010, and what were the consequences? Can Iceland expect more volcanic eruptions in the future? Where can you learn more about these fascinating geological forces? Read on to find out all there is to know about the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption in Iceland.

Why do they call Iceland the Land of Ice and Fire?

Iceland erupts! Photo: LAVAcentre

Colloquially known as the land of ice and fire, Iceland is a volcanic island located in the North-Atlantic ocean.

Its nickname originates from the many volcanoes, geothermal springs and glaciers found dotted across the country.

These features have long added to Iceland’s reputation as a land of beauty and staggering natural contrasts—made all the more noticeable by such cosmic phenomena as

the Midnight Sun and

Northern Lights.

Sat atop a powerful underwater magma plume, it is one of the youngest landmasses on Earth—having first raised above ocean level 18 million years ago—and straddles both the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates.

These tectonic plates stand exposed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Þingvellir National Park—one of the three attractions that makes up Iceland’s popular

Golden Circle sightseeing route.

Visitors walk beside the North American tectonic plate at Þingvellir. Photo: WallpaperFlare.

You can also experience this continental divide on the Reykjanes Peninsula, a region closeby to Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík.

To this day, the country is still deeply affected by this unique geography.

Only in June 2020,

North Iceland has experienced over 4.000 earthquakes,

which hopefully provides some insight into the significant effect these primordial forces still have.

Of all the events that come to define Iceland moving into the 21st century, the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull was one of the biggest.

Together, let’s break down all there is to know about this most significant of volcanic incidents.

What is Eyjafjallajökull?

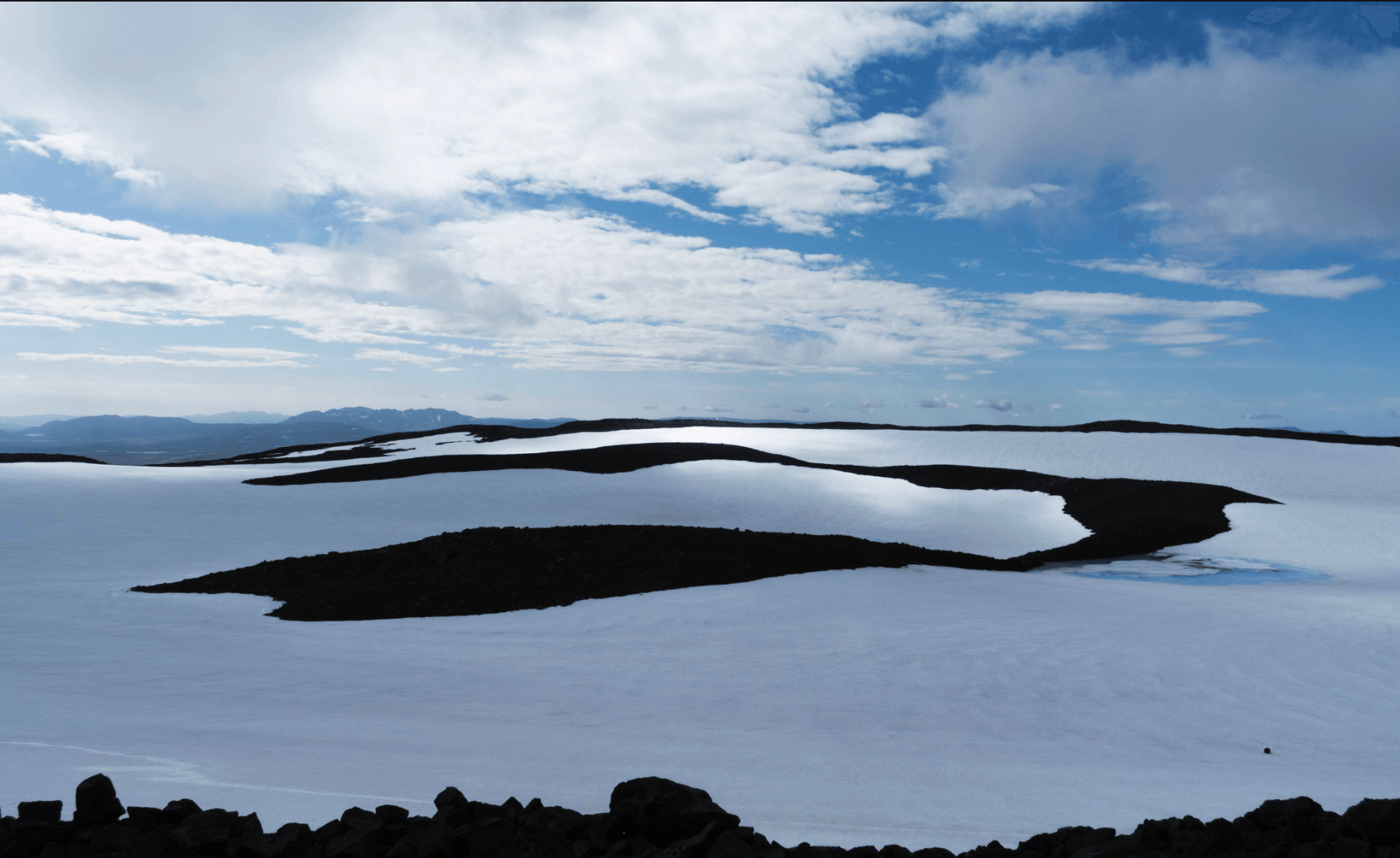

Eyjafjallajökull is one of the many stratovolcanoes found across Iceland. It stands an incredible 1651 metres tall, with a caldera that measures 3–4 kilometres in diameter.

An aerial photograph of Eyjafjallajökull in full. Photo: Wikimedia. CC. TommyBee.

In short, it is a true giant of the landscape; one more than worthy of your time exploring deeper.

Other examples of Icelandic stratovolcanoes include Snæfellsjökull (the Snæfellsnes Peninsula) and Hekla in

South Iceland.

‘Jökull’ is the Icelandic word for

glacier, which is why you will see these letters cropping up again and again when discussing various frozen attractions in Iceland.

In full, Eyjafjallajökull translates to 'island mountain glacier'.

Despites its enormous role in Iceland’s history, Eyjafjallajökull is one of the smaller ice caps found in the country.

The ice sheet that covers Eyjafjallajökull is approximately 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi) in size, thus feeding into countless outlet glaciers, including Gígjökull and Steinholtsjökull.

Eyjafjallajökull during more peaceful times. Photo: Pixabay.

Many tourists are a little confused as to how such concentrated heat could exist beneath a dense layer of ice. (Indeed, it does seem to spit in the face of common sense...)

However, the scientific evidence explains why this occurs. Glaciers are leftover remnants from the last Ice Age, which began around 1.6 million years ago. During this period, huge ice sheets covered most of the earth, shielding entire mountainscapes and valleys beneath them.

Dormant volcanoes do not emit the same level of heat as those that are still active, meaning that the glaciers remain cool enough to remain solid throughout the year.

Given their density, size and high-altitude, paired with annual seasonal changes, glaciers are a permanent fixture of Iceland’s landscape (—though, it should be added, they do face the threat of extinction due to an ever-warming climate.)

Some of our glaciers are even home to the seasonally fluctuating, yet beautiful,

Iceland ice caves. These are frequently at the top of many travellers list - they are only accessible through

Iceland ice cave tours.

As opposed to snow, the ice crystals that compose glaciers are generally much larger—often reaching the size of baseballs. This means glaciers melt much slower than one might expect, with the thawing process left unfinished by the time the winter rolls back around.

When geological heating does occur, glaciers are capable of thawing extremely rapidly. This causes floods of meltwater, known as Jökulhlaup, which can have devastating effects on the nearby area.

Other names for this phenomena include

glaciovolcanos, or

subglacial volcanoes.

Where is Eyjafjallajökull?

Eyjafjallajökull is located in South East Iceland. It is found north of the small village, Skógar, and west of the glacier, Mýrdalsjökull.

Shielded by glacial ice, guests can witness this gargantuan feature while travelling on the

Ring Road—the only road which circles the entire country.

The best option for exploring the region surrounding Eyjafjallajökull is by either taking a fantastic

Iceland self-drive tour or joining one of the many excellent

Iceland South Coast tours.

The stratovolcano can be found at the exact coordinates, 63°37′12″N 19°36′48″W.

How did Eyjafjallajökull erupt?

Eyjafjallajökull at the beginning of the eruption. Photo: Flickr. Bjarki Sigursveinsson.

On the 26th February 2010, the Meteorological Institute of Iceland was forced to deal with a peculiar anomaly in their numbers. According to their readings, unusual seismic activity was noted alongside a rapid expansion in the earth’s crust.

This was evidence that underground magma had begun pouring into the chamber of Eyjafjallajökull volcano.

It should be noted that as far as volcanic eruptions go, Eyjafjallajökull’s was considered fairly small.

How did Eyjafjallajökull erupt?

The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull volcano began with another eruption on the 20th March 2010. In the days previously, scientists had observed over 3.000 earthquakes near the volcano’s epicentre, roughly 7–10 kilometres deep into the earth.

The eruption did not first take place at Eyjafjallajökull’s highest peak—as one might naturally expect—but 8 kilometres east, in an area known as Fimmvörðuháls.

This region marks the boundary line between Eyjafjallajökull and Mýrdalsjökull. The eruption first broke the surface directly atop a popular hiking route in the area, and was expected by those scientists observing the events.

The initial eruptions at Fimmvörðuháls. Photo: LAVAcentre

The Fimmvörðuháls eruption was a lava eruption, where molten magma flowed from an opening in the earth. It created a 200 metre high lava-fall, the tallest one ever measured.

The official end to the Fimmvörðuháls eruption was on 13th of April, 2010. But Eyjafjallajökull volcano wasn’t quite finished.

After a short intermission, the volcano began erupting once more on the 14th April 2010, this time from the top crater. This secondary event was far more dramatic than its predecessor—approximately 20 times as large as the Fimmvörðuháls eruption.

This second eruption was responsible for an ash cloud that reached several kilometres in the air, as well as substantial outburst flooding. This excess meltwater (Jökulhlaup) forced 800 nearby residents to evacuate the area.

The London-based Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre claimed the volcano had stopped erupting by the 21st May 2010. Even so, earthquakes at the epicentre continued to be monitored on a daily basis.

In August, the volcano was officially declared dormant, meaning the eruption lasted approximately five months.

What was the impact in Iceland?

One clear consequence of the eruption was that it reminded Icelanders as to the unbridled power forever bubbling beneath their feet.

Having violently disrupted the general tranquility Icelanders were so accustomed to, this cataclysmic reintroduction no doubt recalled distant cultural memories of former eruptions.

The second fissure ejecting fire! Photo: Wikimedia. CC. Boaworm

This includes the likes of the Laki Eruption of 1783—an event so impactful that many historians claim it was partly responsible for the French Revolution.

During the eruption, over 140 milljónum cubic metres of ash spread over the country, reaching the capital, Reykjavík and even further West to Keflavík Airport.

Two fresh craters were created due to the eruption. These were named Móði and Magni, after the sons of Thor, the Norse God of Thunder.

To commemorate the eruption, the Icelandic post office released three distinctive stamps, each containing actual ash that had fallen on the 17th April 2010.

The Icelandic photographer Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson gained international recognition thanks to his captivating stills of the eruption in progress.

He took over 10,000 photographs of the event, with some of the most compelling taken during helicopter rides directly over the eruption itself. Many of these images were released in a best-selling book titled ‘Eyjafjallajokull: Untamed Nature.’

What was the impact in Europe?

Eyjafjallajökull’s 2010 eruption received significant media coverage around the world.

Aside from showcasing Iceland’s staggering, otherworldly nature, this had the rather amusing consequence of news anchors struggling to pronounce the glacier’s admittedly difficult name.

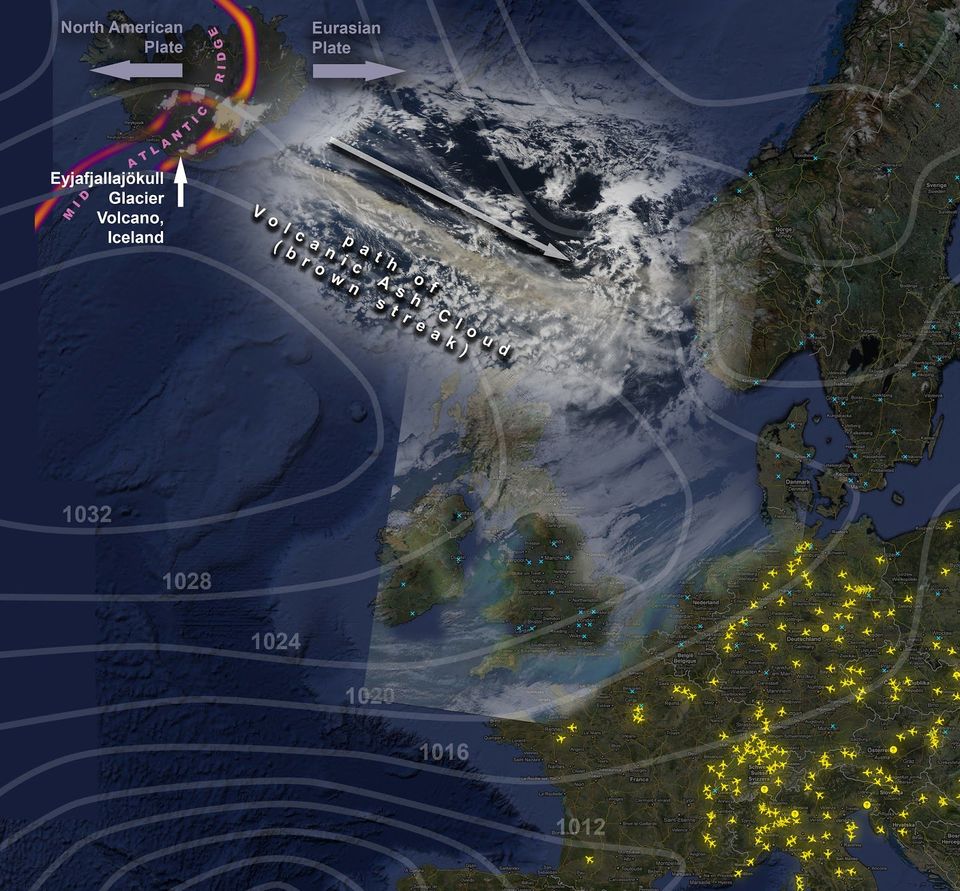

Of course, the impact was, in many ways, no laughing matter. The enormous cloud of ash ejected due to Eyjafjallajökull’s eruption severely hampered European air travel, stranding thousands of put-out passengers.

A map showing Eyjafjallajökull’s ash cloud over Europe. Photo: Flickr. Dominic Alves.

Interestingly enough, many social commentators have claimed that the media exposure the eruption brought upon Iceland is one of the leading factors that contributed to its tourism boom.

Some have even gone as far to say the eruption directly helped bring Iceland out of its economic recession.

Which volcanoes could predict in the near-future?

The prospect that Iceland will experience more volcanic eruptions in the coming years is not a possibility, but an absolute certainty.

There are four volcanoes that have long required a watchful eye.

Hekla is the first of these. The stratovolcano has erupted over 23 times in the last 1000 years, 4 of those happened in the last century.

In the Middle Ages, Hekla was commonly referred to as ‘The Gateway to Hell’—a testament to its lingering infamy and explosive nature.

Anyone who has ever seen footage of, or lava up close, is all too aware how this molten rock can shape itself into appearing like demons and devils desperate to escape to the overworld.

In other words, it’s not difficult to understand why our scientifically illiterate predecessors must have considered terrifying in a biblical sense.

The volcano, Katla, is another of Iceland’s mountains likely to erupt in the coming years.

Only 25 kilometres west of Eyjafjallajökull, Katla is a large volcano and incredibly active, with large-scale eruptions having taken place regularly between 930 CE and 1918 CE.

Historically, eruptions at Katla have occurred with an interlude of 20 - 90 years between them. It has been 103 since the last documented eruption, meaning one is overdue—a fact that Icelanders are all too aware of.

With that said, the area around Katla is one of South Iceland’s biggest attractions, especially its stunning ice caves, available to visit throughout the year -

a tour of Katla ice cave should be on every travellers lists!

Katla erupted in 1918. Photo: Wikimedia. CC. RicHard-59.

Katla is one the largest providers of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the world, constituting up to 4% of the world’s total emissions.

Þorbjörn is a free-standing volcano located on the Reykjanes Peninsula, just north of Grindavík town, near the Blue Lagoon. In January 2020, an unusually large magma-build up (‘inflation’) was observed inside the Þorbjörn volcano, expanding roughly 3-4 mm per day.

It should be noted that there is no immediate concern an eruption will take place. The last to occur in the region took place in 1210-1240 CE, in a period known as ‘The Reykjanes Fires.’

Grímsvötn volcano can be found in the beautiful Vatnajökull National Park, best known for the nature reserve, Skafatfell, and the ‘Crown Jewel of Iceland’, Jökulsárlón glacier lagoon.

The peak of Grímsvötn measures at 1725 m (5,659 ft). It has the highest eruption frequency of any volcano in Iceland. It last erupted in 1998, 2004 and 2011, the last of which saw an ash plume of 12 kilometres in height.

Recently, Grímsvötn began showing signs that an eruption may soon occur. Scientists have recorded more seismic activity and increased geothermal heat than usual, and they believe that an eruption will likely happen in the next weeks or months.

Grímsvötn is located in the Icelandic Highlands, far enough away from inhabited areas to cause great damage. However, ash from eruptions is always a worry as the world learnt in 2010.

It is difficult to predict the consequences of how future eruptions might affect modern-day Iceland, given that it is largely dependent on the size of the explosion and their proximity to densely populated areas.

Conclusion

From a geological perspective, Iceland is one of the most fascinating countries to monitor, observe and explore. With an abundance of powerfully active volcanoes, it’s become part of the way of life for those residing in Iceland to be aware of the chances of the next eruption.

Though

Iceland’s volcanoes since 2010 have earned a position on the centre stage of international news coverage, there has been a regularly explosive past from these geological giants all around the country for millennia.

As much as a visit to the land of fire and ice can include everything from Iceland Whale watching tours to

a glacier expedition, or simply to

hunt the Northern Lights from Reykjavik, you should always be aware of the incredible power that rumbles beneath your feet.

Come and

explore Iceland in 2021 to see the mighty Eyjafjallajökull and so much more for yourself.